Is the world worth fighting for?

This wretched dark world we live in?

DISCLAIMER: This article will need to implicitly mention some disturbing acts in order to have a meaningful discussion on this topic.

Those questions popped up in my head a few days ago when I rewatched David Fincher’s masterpiece, Se7en (1995). I think it’s a must-watch thriller. Go watch it if you haven’t. Let’s explore those questions today in this 6th episode of my Everyday Pilgrim Journal series.

The questions arise from the last line of the movie, where one of the main characters, Detective Somerset, quotes a line from Hemingway’s novel For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Ernest Hemingway once wrote, “The world is a fine place and worth fighting for.” I agree with the second part.

Somerset, Se7en (1995)

The reason the character only agrees with the second part is (without spoiling the movie) because, from his experience: THE WORLD IS CLEARLY NOT A FINE PLACE. The world is a dark and deeply disturbing place. It contains war, death, sexual violence, child trafficking, lies, betrayal, greed, crushing poverty, exploitation, indoctrination, ethnic cleansing, and the slow decay of hope. The list goes on.

Now, to add extra depth to this article, I recently read summaries of Marquis de Sade’s works because many today consider his philosophy and ideas to be the ideal pure form of evil. I am totally speechless at how someone could be so learned, yet so blatantly vile. He imagined scenarios of torture and extreme sexual violence just to entertain his thoughts. That’s the very man you got the word ‘sadism’ from – Sade and sadism.

I am literally trembling at the potential of that man if he was not imprisoned at all. His imagination of evil was overly degenerate, and the worst thing is he could capture them in detailed words, and mask them with the kind of literary techniques you see in masterpieces and classical books in philosophy.

Back to the movie. In the movie’s context a character says:

We see a deadly sin on every street corner, in every home, and we tolerate it. We tolerate it because it’s common, it’s trivial.

Yes, that’s the more disturbing part. The fact that all the extremities of Marquis de Sade’s depravity started growing from tolerating the common and trivial daily “sins” that we all engage in to some degree. If you’re brave enough to face reality, we all participate in and tolerate some of these sins, even if not to Sade’s horrific extent.

When we refuse to shake someone’s hand because we think we’re better looking, it’s pride.

When we feel discouraged after seeing someone more successful than us, it’s envy.

When we wish something bad would happen to someone just because they annoyed us, it’s wrath.

When we take more food than we can possibly eat at a buffet, just because it’s there, it’s gluttony.

When we look at someone not as a person, but as something to be had, it’s lust.

When we have more than enough but are unwilling to share even a little, it’s greed.

When we know what we need to do but keep scrolling on our phones instead, it’s sloth.

Now let’s address the second part of the quote: “The world is… worth fighting for.” However, based on our discussion so far, I think a more logical conclusion would be: “The world is so evil that humanity should become extinct, and we should not pass on our genes at all” (extreme antinatalism).

But, despite all the darkness and “bad stuff” in the world, there seems to be this innate human tendency to survive and pass down our genes. This gives rise to the idea of natalism, the counterpoint to antinatalism. But why does this drive persist, even in the face of so much suffering?

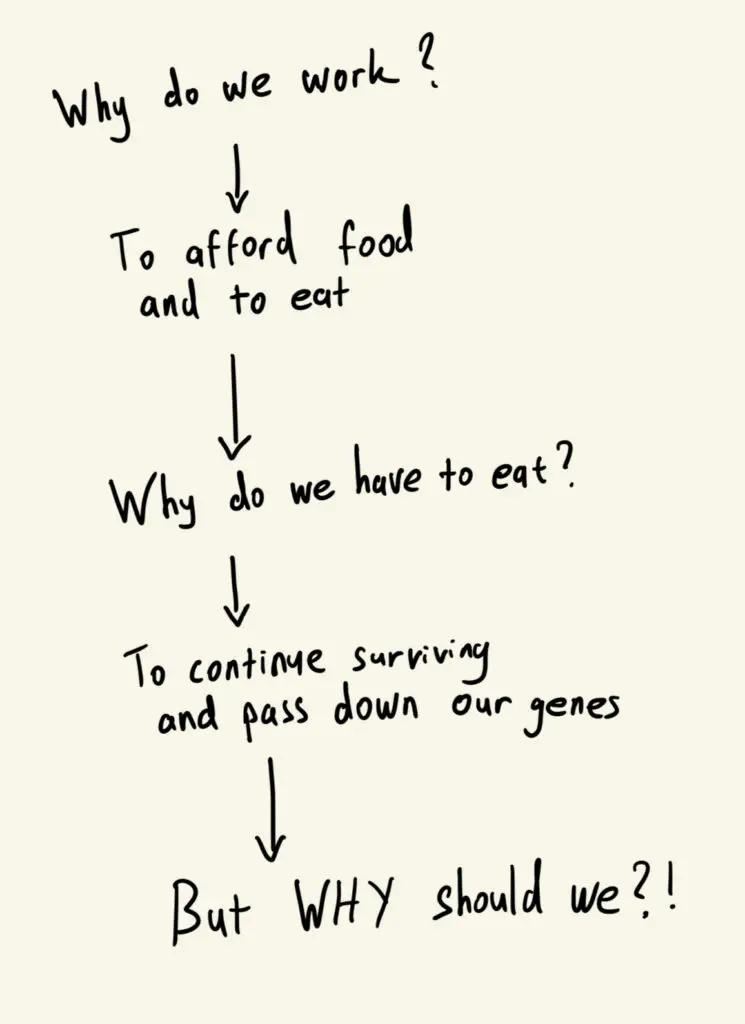

People with faith in naturalism often stop at the simple explanation: “We want to continue living to pass down our genes. Nothing more. Full stop.” But this raises another layer of questioning.

Why do we have this natural tendency to pass down our genes in the first place? What compels our bodies to oblige us to do so? Why should we pass down our genes?

Why why why why…?

Let me repeat. Because using logic and pure rationality, the answer to suffering is non-existence. If we are just biological machines driven to pass on genes, and this process is filled with the suffering and “trivial sins” we see everywhere, then choosing to end the cycle is a rational act of compassion. Why force another consciousness to endure a world of such darkness for no ultimate reason? The fight isn’t worth it because the game is rigged from the start. So, is that it? Is the most profound answer humanity can find simply to… quit?

It is precisely here that David Hume introduced the “is-ought problem,” it reveals that one cannot derive what ought to be merely from what is. In simpler terms, observing nature alone cannot tell us what is morally right or wrong. In other words, looking at the world as it is cannot tell us what is morally right or wrong. This gap between facts and values sets the stage for the arrival of a most unusual figure.

Into this world of self-preservation, pride, and wrath, walks a figure whose entire life’s logic is an inversion of our own. A poor carpenter from a forgotten corner of the Roman Empire. He is the great anomaly. Which is Christ himself. No. He’s not exclusively a religious figure or icon for Christians, but rather a historical and philosophical “glitch” in the Matrix for everyone (nihilists, naturalists, idealists, agnostics, atheists, Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, and others).

His teachings are not just difficult. They are fully out of this world and purely insane from a survival-of-the-fittest perspective. They are the opposite of every strong leader you could name, yet his views changed the world. His birth year became the main standard turning point for civilized history, and his influence laid the groundwork for medieval monasteries that preserved knowledge, leading to the first universities in Europe. Without this foundation, we wouldn’t have Oxford, Cambridge, the Ivy League, or the scientific revolution. He preached weakness as strength, defeat as victory, and death as life. The very concepts that should have died out immediately in any ‘realistic’ practical society, but instead reshaped human civilization.

- To a world built on wrath and retaliation (“an eye for an eye”), he commands us to turn the other cheek.

- To our innate pride, this man, who claimed to be God, chose to materialize himself in this world by being born in a dirty manger. He also knelt and washed his followers’ dirty feet.

- He didn’t just condemn evil actions; he went straight to the “trivial” source. He taught that lust in the heart is already adultery, and anger toward a brother is already murder. He saw the seed and called it the tree.

- And then, in the face of the ultimate evil (betrayal, torture, and a brutal public execution of crucifixion) his final act is not a curse, but a plea for forgiveness: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” This is the ultimate foolishness. It’s a love that makes no worldly sense at all. It’s too overwhelming to even imagine such love.

In a world where we slowly walk and cling toward the direction of Marquis de Sade’s ideals (to be a libertine, to enjoy pleasure as much as possible, to hurt others for pleasure, to only care for our own pleasures, no meaning, only pleasure, pleasure, pleasure, pure pleasure), there’s this insane antithesis – the Christ.

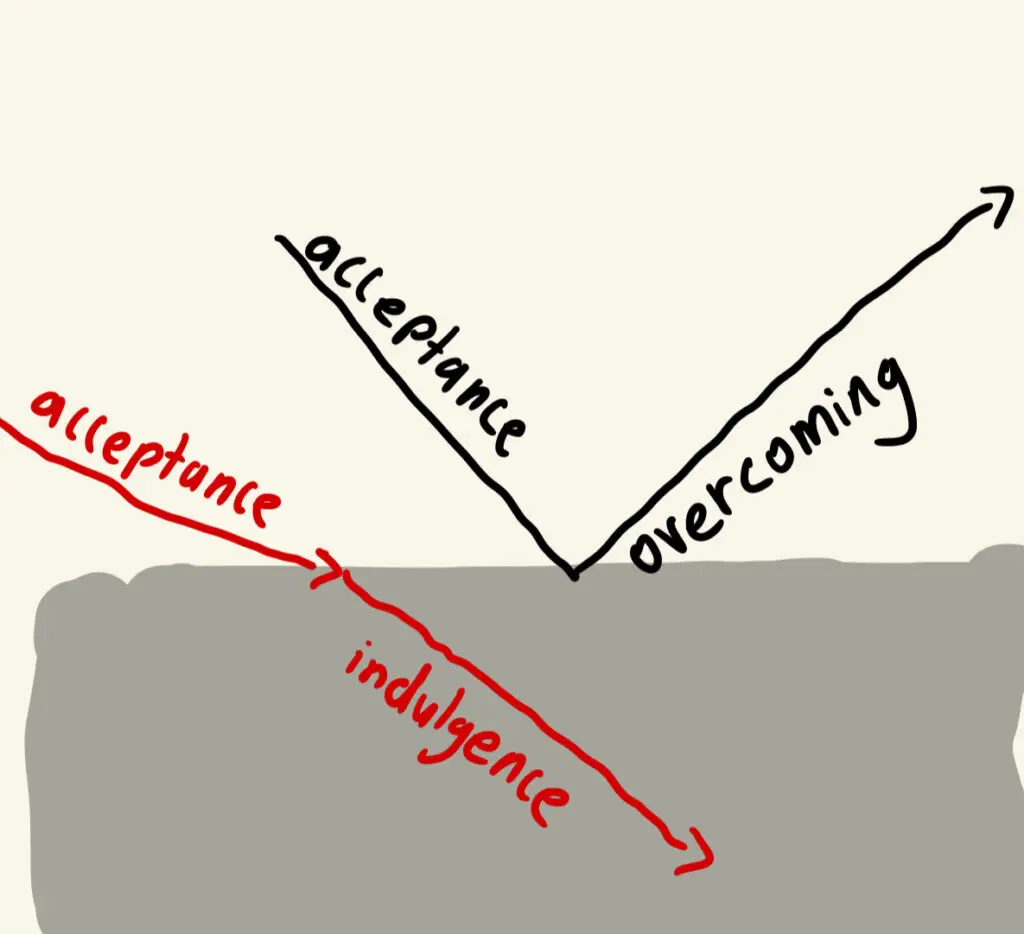

His testimony is beautiful not because it ignores ugliness, but because it embraces it. Not to indulge in it like de Sade, but to transcend it. It proves there is a force more powerful than suffering and death: a selfless, forgiving love that accepts our dark reality without despairing, absorbing the darkness itself.

This love reveals why the world is a fine place, but not because it’s comfortable or safe. St. Augustine saw our world as a place where two cities are entangled: the earthly city built on a prideful “love of self,” and the heavenly city built on the “love of God.” The world is a fine place because it is the arena for this conflict. It’s the dark canvas that makes a single act of forgiveness so blindingly beautiful, confirming his idea that:

For God judged it better to bring good out of evil than to suffer no evil to exist.

–St. Augustine of Hippo

This is why the world is worth fighting for. We aren’t trying to build a pain-free fantasy utopia. We are fighting to defend the possibility of this foolish love, for the space where grace can happen.

And this fight happens on the “trivial,” daily level: choosing to be happy for someone’s success instead of envious, sharing what we have instead of being greedy, and seeing another person as a soul, not an object.

We fight because Christ proved it was worth it, he didn’t just talk about it. He entered the darkness to plant a light that cannot be extinguished. Detective Somerset was right to fight, but perhaps for a deeper reason than he knew. The world is worth fighting for because love, in its most foolish and divine form, is real and present within it.

That is the beauty.

That is the hope.

Leave a Reply