Have you ever watched the movie or read the story The Curious Case of Benjamin Button by F. Scott Fitzgerald? It’s about a man who ages backward: he is born old and grows younger in appearance and physique as the years pass, ultimately dying as an infant. The story brings to mind the saying,

“Youth is wasted on the young.”

It’s a sentiment shared by every older generation looking back to the youth or even on their own past, and it contains a raw, paradoxical truth. But I’d argue it doesn’t just apply to the young; it applies to anyone who is merely existing instead of truly living. Perhaps a better way to say it is:

“Life is wasted on the living.”

Let’s talk about why, and what we can do about it, in this 7th episode of the Everyday Pilgrim Journal (EPJ) series. We’re going to talk about time.

Our journey begins with time itself. We build amazing clockworks, measuring our days with a complex arrangement of minuscule gears. But we shouldn’t let this mechanical precision mask us from the nature of “time.” A clock can measure time, but what in the world is time itself?

The Mysterious Property and Nature of Time

About a month ago, I had a conversation about mathematical axioms. The person I spoke with insisted that everything he does is perfectly rational. He told me that the world is fully intelligible through modern science and reason. He argued, for example, that the area of a triangle will always be one-half its base times its height, and that this certainty leaves no room for “faith.”

But does it? Does the ability to measure something mean we completely understand it in all its layers? To calculate the area of a triangle, we must accept certain conventions, these are what we call axioms. As the French Mathematician, Henri Poincaré wrote:

“The sublime truths of which we spoke are, at bottom, nothing more than a catalogue. We have a great number of books in our library; we have written their titles on slips of paper and we have arranged them in a certain order. The law of gravitation is one of these slips… It does not teach us the true nature of things, any more than the title of a book on the catalogue teaches us what is in the book.”

He also wrote:

“The axioms of geometry, therefore, are neither synthetic a priori judgments nor experimental facts. They are conventions; our choice among all possible conventions is guided by experimental facts, but it remains free and is limited only by the necessity of avoiding all contradiction.”

In other words, mathematical certainty often rests on choices we agree to make. Measurement can be precise, yet the foundations that make such precision possible are still, in a meaningful sense, conventions.

Hence why we should ponder time, too. We have clocks—atomic clocks, sundials, you name it—to measure time, or at least to interpret it. But a simple question remains: what is time, really?

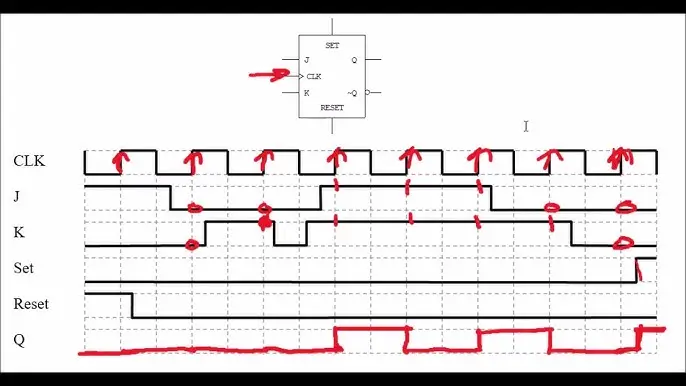

As an electronics engineering student, I’m very familiar with the concept of a clock signal, or CLK, that synchronizes every computation inside a computer. But this idea of a governing frequency extends far beyond electronic behavior. You can see it in the steady RPM of a car’s engine, the tempo a conductor sets for an orchestra, and even in the rhythm of our own heartbeats and strides. Modern physics tells us that at the most fundamental level, every particle vibrates. It’s just as Nikola Tesla famously said:

“If you want to find the secrets of the universe, think in terms of energy, frequency and vibration.”

This universal pulse makes you feel as if everything is, in a way, musical. We are constantly syncing ourselves to different frequencies, the beat of a song, the schedule of a workday, the natural cycle of the seasons. There’s a deep sense of harmony when our personal rhythm aligns with the world around us, and a jarring dissonance when we fall out of step. It’s as if time itself isn’t just a measurement or a man-made concept, but the ultimate clock signal, a grand, silent metronome embedded into the very fabric of reality.

Yet, for all its presence, time remains a weird mystery. Throughout history, the greatest minds like philosophers, scientists, and writers have tried to define it, but it’s still a blurry concept. Is it a set of experience, a perception, a wave, a particle, an energy? We still don’t fully comprehend it. Most of us aren’t mad scientists with labs to build a time machine, but I believe we can ponder it enough to learn how to use it.

Because while we can’t define it, we certainly feel its effects. We wait for payday, we carry trauma from the past, and we hold onto hope for the future. We can only be aware of the “now” because of the present moment. But that moment is always ticking away. Time is ruthless; it doesn’t wait for anyone. When we are young and healthy, we often think our time is endless. The irony is that nearly every older person has regrets. “I wish I hadn’t driven so recklessly.” “I wish I hadn’t treated my parents that way.” I’m sure even if you’re young, you have a missed chance or a mistake from the past that sticks with you.

Unfortunately, time doesn’t care. It just keeps ticking. If it were to stop during our happiest moments, we couldn’t truly experience that joy. But if it were to stop during our worst moments, we would never know what happiness might be waiting for us. It won’t even stop if you sit still for 10 hours and just think; your very neurons need to operate and interact within time. Time is simply there, cold and indifferent.

I experienced this myself recently. For weeks, I had a routine of waking at 4 AM for prayers and exercise. This early morning discipline was optimizing my whole day. However, last Sunday I overslept and missed it all. That one slip-up had a big impact, and for the last few days, I’ve abandoned that discipline, feeling a minor sadness. But as I feel this, I see that time doesn’t care. With its steady beat, it just persists.

And while writing this, I’m starting to understand again. Because time does not care, it is up to me to care. It all comes down to my perception. The sheer complexity and simplicity of time can lead to a nihilistic view, to just use it without purpose. But the truth is that it is both overly mysterious and deeply meaningful.

That’s why we need to number our days. Not just by being aware of the date on a calendar, but by choosing to live mindfully. This brings me to a powerful request from Psalm 90:

Teach us to number our days,

that we may gain a heart of wisdom.

“Numbering our days” isn’t just about knowing the date or counting down a calendar. It’s about mindfully looking at our inner compass and choosing to live each day according to it, not just letting the moments slip away. We are all born into certain bodies, families, and circumstances, but that doesn’t mean we are stripped of our ability to decide.

Even a hardwired atheist like Richard Dawkins, who argues we are machines built to merely replicate our genes, hints at this mystery. In his book The Selfish Gene, he writes

“We are built as gene machines… but we have the power to turn against our creators. We, alone on earth, can rebel against the tyranny of the selfish replicators.”

Wait, what? He seems to contradict himself. If we are purely molecules, what part of us is capable of this rebellion? What allows us to fight our natural tendencies—the impulse to be cruel, to hurt others, or to simply waste our time mindlessly? We recognize this fight against our programming and we call it good.

Yes, there is a part of us that gives us a choice. So let’s choose to number our days, to live every minute with meaning.

I believe we can all participate in this rebellion, regardless of our circumstances or the things we can’t control. It begins with the simple choice to reject shallow, mindless activity. We can make sure that whatever we do has a story to tell, no matter how small or insignificant that story is. A story of you finishing a 15-minute run is far more noble than a story of you scrolling for three hours.

Of course, there’s a common objection to this. You might think, “It’s easy to talk about using time well, but my schedule is predetermined by the system. I have to work to survive.” That’s true. We live in the real life and no economic system allows someone to live without some kind of work; it’s a fundamental part of reality we can’t escape.

But this is precisely why “numbering our days” is so important. The rebellion against the “tyranny of the selfish replicators” isn’t about escaping work or reality. It’s more about what we choose to do within that reality. It’s in the small, intentional choices we make in the pockets of time that we do control.

It is NOT OVERTHINKING

Some might say this level of attention is overthinking, but it isn’t. It’s simply recognizing that every minute counts and that putting effort into the good we do with that time is worthwhile. It’s an acknowledgment of that unique human ability Richard Dawkins himself pointed out, “We, alone on earth” can rebel against our base programming.

Don’t underestimate this capacity. The ability to choose meaningful action is more important than any external advantage. I would argue that a simple rural farmer who uses his time with purpose can do far more good for himself and others than an internet-addicted nihilist who, despite all his massive knowledge, wastes his life away.

This choice to live with purpose is seemingly simple, and to a cynical world, perhaps foolish. But it’s also beautiful, which is the recurring theme of this EPJ series. As always, we tie this back to Christ. Why? Because his life is the ultimate example of this rebellion. The fact that we have a multi-billion dollar industry of time-management and disciplinary motivational speakers shows that we struggle to rebel against our natural tendencies that favor mindlessness.

We need more than just tips and tricks; we need an inner transformation. This is an idea the psychologist Carl Jung spent his life exploring. It’s why the figure of Christ is so powerful, even within a secular or psychological framework. Jung saw Christ not just as a historical or mythical figure, but as a profound symbol of the human psyche’s potential for wholeness. In his book Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, Jung wrote:

“The Christ-symbol is of the greatest importance for psychology in so far as it is perhaps the most highly developed and differentiated symbol of the self, apart from the figure of the Buddha.”

What Jung meant by the “self” wasn’t our everyday ego, but the complete, integrated person we have the potential to become. He argued that within our psyche, this archetype of the whole person exists. For him, the symbol of Christ represents this perfectly.

This connects directly back to “numbering our days.” That mysterious “part of us” that can rebel against our selfish programming is what Jung would call the drive toward the Self. It is the deep, innate desire to become whole rather than fragmented. When we choose to perform a small, meaningful act instead of wasting our time, we are taking a practical step in that inner transformation. We are allowing our conscious desire for meaning to guide our unconscious, chaotic impulses.

Christ’s life, then, becomes more than just a moral example. From this perspective, it’s a psychological blueprint for a life lived with complete intention. It is the ultimate rebellion against a fragmented existence and the ultimate model for a life where every moment counts.

This psychological transformation has a deep parallel in theology, particularly in the Eastern Christianity idea of theosis. This is the process of becoming more ‘like God’. The idea is that through a spiritual rebirth, we are given a new inner “DNA”—the DNA of God—which empowers our rebellion against our base tendencies, in this case the tendency to be lazy and waste our time.

Christ’s own life is the ultimate proof of this principle. His ministry was only about three years long, yet it changed the course of human history. He was able to create such a massive impact because he never wasted a moment on sloth; he made every minute of those three years count.

So let’s choose to transform. Slowly but surely. It may feel monumental, but I believe it’s possible if we humble ourselves to face what’s right in front of us each time. Change happens one step at a time, every minute, every second, because we can only conquer what’s before us, nothing more. Yet it all adds up if we keep choosing it, moment by moment.

Let’s begin numbering our days.

Leave a Reply