“You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.”

–St. Augustine of Hippo

At the time of the writing of this article’s first draft (August 2025), Indonesia, where I currently live, is in a pathetic state. There are endless protests, violence, and fake news designed to manipulate and spread hate. So much noise. And even without the negativity of the news, this is still our reality. We are constantly distracted by notifications and pings from our smartphones and entertainment. We’ve grown so used to this way of living that we no longer allow ourselves to be bored. This generation is afraid, almost petrified, of boredom and silence.

Even when we take our phones out of the equation, our minds can entertain themselves with endless fantasies, fake scenarios, and constant inner monologues that possibly hurt us and others.

Someone accidentally gave us a frown, and we think to ourselves, “That weak guy is trying to start some beef with me!” That trivial expression turned into an unnecessarily strong hate inside us.

Positive fantasies are also able to bring us into unhealthy anxiety, where we compare ourselves with others and with ideals we create in our heads.

Believe it or not, this state of internal conflict (I love to call it pseudo-scizophrenia) is the root of most of our problems. We normalize it by generating a constant stream of unhelpful commentary and then tell ourselves a convenient lie that these inner monologues are the very proof of our rationality.

“There are more things … likely to frighten us than there are to crush us; we suffer more often in imagination than in reality.”

–Seneca

This is why silence is critical. Not just physical silence but also the silence within us.

We often label silence as passive and inactive. Yet passivity and inactivity can feel strangely difficult when we choose them intentionally. It feels as though we’re making no progress. I can relate to this tension. My friends are constantly updating their CVs and LinkedIn profiles; some are relentlessly applying for jobs, while others are promoting their businesses nonstop, and then some do nothing but passively consume the surrounding noise.

I’m not saying that being responsible or diligent is wrong. Work and effort are essential for survival in any kind of economy, and I strive for that in my own daily life as well. But I want to point to something beyond mere productivity.

In this 8th episode of my Everyday Pilgrim Journal (EPJ) series, I want to highlight an idea our modern culture has largely forgotten: the urgent necessity of grounding ourselves in silence. To today’s standards, this may seem foolish or even alien to some. Yet I believe it is more important than ever. Let’s explore the significance and the beauty of silence together, through art, philosophy, science, life in general, guided by the insights of a beautiful book I discovered a few months ago: Into the Silent Land by Father Martin Laird. Though written from Augustinian wisdom and a Christian perspective, I believe its vision is universal enough to resonate with anyone, regardless of background.

There is No Existence Without Nothingness

You see, in Indonesia, we have the word ‘sembahyang’, usually translated as ‘to pray’ but literally means ‘to worship hyang’. Now, what is Hyang? It is not a personified deity like the Dewa (gods). Instead, as explained by a Pasundan spiritualist, Abah L. Q. Hendrawan, Hyang is defined as the primordial void, the cosmic emptiness, the fundamental nothingness that paradoxically contains and precedes all existence. It is the formless, ultimate reality that can never be visually depicted precisely because it is nothingness.

Therefore, to sembahyang is to humbly honor this sacred emptiness. This is the crucial link our modern culture has severed. We fear inactivity and silence because we mistake this essential void for a useless vacuum. But this ancient wisdom teaches us the opposite.

Silence is not an absence; it is a direct encounter with the creative potential of the void (the Hyang). Hendrawan uses the analogy of breath: we are sustained by the invisible air, an emptiness we cannot see but which is vital for life. In the same way, grounding ourselves in silence is not a passive act of making no progress. It is the active practice of clearing space to perceive the fundamental reality that noise and busyness constantly obscure.

Nothingness exists to contain things. It sounds like a paradoxical, mind-bending idea, but think about it. Matter can only exist because there is empty space around it, giving it room to be. Without the void, there would be no place for anything to appear. That’s why negative space is so important. Not just in science, but also in art, design, and even life itself. It’s a concept we need to grasp clearly, and we’ll see more of its relevance as we go.

Negative Space in Art

1. Music

We see the same idea in music and music composition.

“It’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don’t play”

–Miles Davis

The quote can be interpreted in many ways, but let’s keep it simple. Imagine if all music were played entirely in legato, with every note connected continuously non-stop until the end. There would be no tension, no moments of quietness to let you breathe and fully enjoy it.

It basically means that music is not only about the notes you hear, but also about the ones you don’t. If every beat and every space between beats were filled with sound, the result would collapse into an undifferentiated and oppressive noise and cacophony.

Without silence between the notes, there can be no rhythm. Rhythm is shaped not only by the notes that sound but also by the measured pauses that give them meaning and emphasis. Without silence, every piece of music would be as plain and dry as hardtack. And this rule applies to every kind of music, pop, classical, jazz, folk, bossa nova, etc.

Are you still not aware of this? Let me invite you to listen to fine music for a clear example.

This is So What by the legendary Miles Davis. Notice how it uses silence between the notes at the beginning, almost as if pulling your curiosity and attention toward the music. From there, it gradually builds, and in the middle, you can hear every instrument coming alive. But pay close attention. Silence is always present, shaping the music. Each instrument is enjoyable to hear because there are measured pauses between the notes. Imagine if the trumpet kept playing nonstop without any pauses. It would sound messy, exhausting, careless, and I would even say ‘lazy’.

2. Paintings

Let’s see how this applies to visual art, such as paintings.

Take a good look at these two examples. Both are beautiful. The first is painted with soft, layered shades that give the impression of water or perhaps the sky. But the second tells a much deeper story.

The painting on the right makes deliberate use of negative space. That empty area on the right creates a striking sense of intensity. This is not just water; this is The Great Wave. The vast, threatening wave, which fills the positive space, feels even more dramatic and powerful because of the balance created by the negative space. It keeps the scene from becoming chaotic. The tiny Mount Fuji in the background, framed by the curve of the wave, adds a breathtaking sense of scale and depth. The first painting delights you with its colors, but the second one makes you say, Wow.

Again, I’m not saying the abstract painting is bad. It simply shows how the use of negative space can create a much stronger impact. Ironically, the mockup of the abstract painting on the left is arguably beautiful because of the liminal space created by the white wall, lol.

3. Theatre

Now, let’s get to our final example in art. There are still many, but I choose to stop here because I think I have already made myself clear with the two previous examples. Let’s have a look at this movie scene from No Country for Old Men.

Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), a relentless and seemingly unstoppable killer, stops for gas at a remote, dusty Texaco station. The elderly gas station clerk behind the counter tries to make friendly, idle small talk about the weather and his business.

The conversation quickly turns unnerving. Chigurh doesn’t follow the normal rules of casual conversation. He answers awkwardly, stares intently, and begins to ask personal, probing questions that make the old man increasingly uncomfortable.

The tension escalates when the gas station clerk mentions that he married into his business. Chigurh psychopathically latches onto this, seeing it as an act of chance that determined the man’s entire life. This leads him to place a quarter on the counter.

Gas Station Clerk: So, what’s the deal on this?

Chigurh: It’s a coin.

Gas Station Clerk: What do I stand to win?

Chigurh: Everything.

Gas Station Clerk: How’s that?

Chigurh: You have to call it. I can’t call it for you. It wouldn’t be fair.

It ends with the old man nervously calling “heads” and winning the toss. The relief is immense. Chigurh simply takes his quarter and leaves, advising the man not to put the coin in his pocket, because “it’s your lucky quarter.”

The scene is terrifying not because of any violence, but because of the psychological pressure cooker created by the dialogue’s calculated and predatory silences that Chigurh employs. The true horror lies in the emptiness between the words.

Negative Space in Philosophy

1. Eastern Philosophy

In many Eastern traditions, emptiness is not a void to be feared but a potent, fundamental state of being. It’s seen as the source of all potential and a state to be cultivated for wisdom and peace. This is very similar to the idea of Hyang from the intro of this article!

Taoism (道教) and the Uncarved Block: Taoism, particularly in the Tao Te Ching, celebrates the power of the “empty” and the unformed. A central idea is the usefulness of what is not there. For example, it is the hollowness of a bowl that makes it useful, the empty space in a room that makes it livable, and the hollow hub of a wheel that allows it to turn. The ultimate reality, the way, the Tao, is itself described as an empty, formless, and silent source from which all things in the universe arise (sounds very much like Hyang). The goal is to return to this state of simplicity and potential of the “uncarved block.” The silence represented by the uncarved block is therefore not an absence of sound, but a metaphysical silence. It is a silence from the inner clamor of the ego, from the constant mental chatter of dualistic judgments (good/bad, success/failure), and from the anxiety of perpetually striving to “become” something. The noise of the world, in this sense, is the very process of naming, categorizing, and desiring, which fragments our original, unified nature.

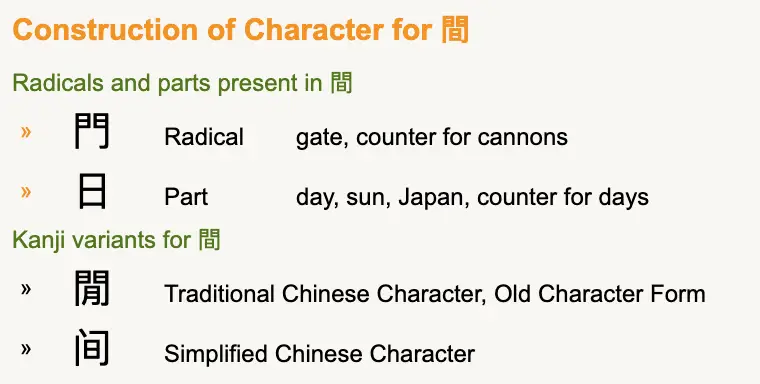

Buddhism (佛教) and Śūnyatā: In Buddhism, the concept of Śūnyatā (शून्यता), or “Emptiness,” is central. This doesn’t mean nothing exists; rather, it means that all things are “empty” of any permanent, independent, or inherent self. Everything is interconnected and in a constant state of flux. Realizing this “emptiness” frees the mind from attachment to fleeting things, reducing suffering. The practice of meditation is a direct application of this: by creating a “silent space” in the mind, one can observe reality more clearly and achieve a state of inner peace. Zen Buddhism further expresses this in aesthetics through the concept of Ma (間), the intentional use of empty space in art and design to create focus and harmony. The kanji character 間 is really powerful in how it captures this idea visually. It combines the symbols for “gate” (門) and “sun” (日), which creates this vivid image of sunlight streaming through the crack of an open door. So right away, you get this sense of emptiness as a space full of potential, not just a plain nothingness. It’s an opening for light and revelation to come through.

I’m sorry, but let me show you another art. Particularly, this Japanese painting demonstrates the idea of Ma (間).

Look at the vast, unpainted areas of mist and air. They are not merely background; they are as vital to the composition as the trees themselves, creating atmosphere, depth, and a sense of stillness.

2. Western Philosophy

In Western philosophy, “nothingness” has often been viewed with more anxiety, but it’s also been framed as the very condition that allows for human freedom and the appearance of truth.

Existentialism and Freedom: For existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre, “nothingness” (le néant) is at the core of human consciousness. Unlike a rock, which simply is what it is, humans have no fixed essence. We are “empty” of a pre-determined nature. This very emptiness, this “nothingness” at our center, is what makes us radically free. It’s the silent gap between a stimulus and our response where we must choose who we will be. This freedom can cause anxiety (Angst), but it’s also what makes a meaningful life possible. We are condemned to be free and must create value in a universe that seemingly offers none on its own. This is possible because of the negative space.

Phenomenology and the “Clearing”: The German philosopher Martin Heidegger used the metaphor of a “clearing” (Lichtung) in a dense forest to describe how truth and being are revealed. This clearing is not a “thing” itself but an open, empty space that allows things to appear as they are. For Heidegger, this fundamental “openness”—a kind of philosophical negative space—is more fundamental than any object or being that appears within it. We must be receptive to this silent clearing to truly understand existence.

So, we’ve seen how silence and empty space are not voids, but active, essential elements in art, music, philosophy, and daily life in general. They provide contrast, create meaning, and define the very subjects they surround. But this principle is not just an abstract theory for artists and thinkers. It has a direct, measurable, and real impact on our daily lives, especially on the very wiring of our brains and our capacity for genuine creativity.

Negative Space in Daily Life

First, we need to reframe our relationship with boredom. In our culture, boredom is seen as a problem to be solved, an uncomfortable void to be immediately filled with a podcast, a social media scroll, or any other distraction. But what if boredom isn’t the problem, but the pathway? When we deliberately allow ourselves to be bored, we create the necessary space for our minds to wander, make novel connections, and stumble upon new ideas.

Historical figures like Isaac Newton didn’t have their breakthroughs while frantically multitasking. In the famous anecdote, Newton reportedly conceived of universal gravitation while sitting under a tree, in a state of quiet contemplation. By running from boredom, we are actively robbing ourselves of one of the most potent catalysts for creativity.

This modern insight aligns perfectly with what neuroscientists have discovered about the brain’s “resting” state. When we’re not actively focused on a task, our brains aren’t “off” at all. Instead, a specific network called the Default Mode Network (DMN) becomes highly active. This is the brain state linked to our most human qualities: self-reflection, memory consolidation, and empathy. It’s where our brain connects disparate ideas and reflects on our past and future. In short, silence and “boredom” are when our brain does its most important work on defining who we are. This is absolutely essential for any deep learning or creative process. As author Barbara Oakley explains in her book A Mind for Numbers, this is the brain’s “diffuse mode of thinking”—the relaxed state where breakthroughs happen. (I wrote a summary of this book in my previous post)

That is also why, to learn skills effectively, you need to take silent breaks after practicing or training. As American neuroscientist Andrew Huberman explains in his podcast here, these moments of stillness mysteriously allow the brain to consolidate what you’ve learned effectively.

On a more immediate level, silence is a biological antidote to the constant “fight-or-flight” state induced by our noisy world. Scientific studies have shown that deliberately entering a state of silence can lower our levels of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, physically calming our entire nervous system. This is a core reason why practices like meditation, breathing exercises to calm down, or even a short nap show tangible results.

Do quick searches on Google Scholar for these papers if you want to know more:

- Pascoe, M. C., Thompson, D. R., & Ski, C. F. (2017). Yoga, mindfulness-based stress reduction and stress-related physiological measures: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 86, 152–167.

- Bernardi, L., Porta, C., & Sleight, P. (2006). Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory changes induced by different types of music in musicians and non-musicians: the importance of silence. Heart, 92(4), 445–452.

- Kox, M., van Eijk, L. T., Zwaag, J., van den Wildenberg, J., Sweep, F. C., van der Hoeven, J. G., & Pickkers, P. (2014). Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(20), 7379–7384.

- Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225.

When people feel significantly better after taking a break from constant sensory stimulation, it’s not just in their heads; their bodies are being given a precious opportunity to stand down from a state of high alert and begin to heal.

The Why: Embracing Reality in Its Fullness

In the end, why ground ourselves in silence? It’s about the details. This practice of cultivating internal silence is more than just a psychological life-hack or a biological reset. In the Christian contemplative tradition, it is the act of preparing the soul’s most sacred space. This brings us to the ultimate reason for grounding ourselves in silence. It’s about engaging with the totality of our reality.

As I’ve explored many times in this series (Everyday Pilgrim Journal), reality isn’t as straightforward as it seems. For instance, consider our experience of beauty. If the universe were purely materialistic, how could we account for such a feeling? In that view, concepts like law and crime would be meaningless, as an act of murder or sexual violence would simply be one set of molecules interacting with another.

We exercise, eat, and work to preserve our bodies and minds, but as Saint Thomas Aquinas taught, our nature is composed of more than these visible parts. He distinguished between the ratio inferior—our logical, discursive mind concerned with worldly affairs—and the ratio superior, the highest aspect of our intellect oriented toward God.

It is this capacity for the divine that fuels our longing for eternity and makes humanity unique. While animals are driven by the simple need to survive and reproduce, humans strive to study and conquer what we see, build lasting legacies, create masterpieces, and worship the transcendent. This impulse is the very expression of being made in the divine image (Imago Dei), as described in Genesis 1:26.

Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.”

Genesis 1:26

The desert ascetic Evagrius called this the nous. In the scriptures, it is usually referred to as ‘spirit,’ or ‘pneuma,’ as in John 4:24 and 1 Thessalonians 5:23. Whatever the name, this is the faculty that connects directly with the divine, the highest part of reality.

We access it only when we enter into silence, specifically inner silence. When we ignore this third, deepest part of ourselves, we inevitably feel that something is off, that a fundamental part of our being is unfulfilled.

This is why grounding ourselves in inner silence is not being extra or some niche new age trend. Rather, it is a fundamental necessity, as essential to our well-being as eating, sleeping, and seeking recreation. Through it, we enter pure awareness, perceive the divine, and, as Saint Augustine beautifully put it, “fly to our beloved homeland.” This homeland is not a place, but the very source of our being—that which, in the words of Father Laird, “[the] homeland that grounds our very selves.”

“We must fly to our beloved homeland. There the father is, and there is everything.”

–St. Augustine of Hippo

When we return to our true homeland within, a peace settles over us, for it is where we truly belong. Life’s adversities will not cease—the death of loved ones, personal failures, the hatred of others—yet slowly, surely, we learn to respond to them with a new stillness.

As this inner practice deepens, we become like Mount Zion. The weather around it can be stormy, cloudy, or violent, but the mountain itself stands firm, unmoved. We begin to realize that we are not the fleeting weather, but the enduring mountain.

Those who trust in the Lord are like Mount Zion,

Psalms 125:1

which cannot be moved, but abides forever.

This result is not something we achieve; rather, it is something already within us. We just need to clear the noise, clear the smoke, and remove the veil. It is very close, it is within us. St. Augustine says it is “closer to me than I am to myself.”

–St. Paul

“But when one turns to the Lord, the veil is removed.”

This resilience is an art, practiced with the skill of a sailor and the patience of a gardener. The wise sailor does not command the wind; he masters the sail. He cannot change the unyielding tides, but he can set his course. Likewise, the gardener does not force the seed to sprout, but humbly creates the conditions for growth—watering the soil and protecting the life within it.

We come to see that we are not defined by the unpredictable weather of our lives, but by how we tend to the garden of our heart and navigate the seas of our existence.

“I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth. So neither he who plants nor he who waters is anything, but only God who gives the growth.”

–St. Paul

Ultimately, this practice brings us closer to a higher reality. As Genesis 1:26 says, we are made to reflect the image of God. Through this daily work, we begin to express the way of Christ in our lives. It is a lifelong journey. The more we face pain and temptation with this stillness, the more we are purified and transformed. This is theosis: the process of becoming more like Christ, embodying divine virtues in our human lives.

Others will begin to feel it. Our presence will bring a sense of peace. Just as Christ “increased in wisdom and in stature, and in favor with God and man” (Luke 2:52), we too can grow in this grace.

“For the Greeks, by going abroad and crossing the sea, learn letters, but there is no need for us to go abroad for the sake of the kingdom of heaven, nor to cross the sea for the sake of virtue. For the Lord has told us before, ‘The kingdom of God is within you’ (Luke 17:21). Virtue, therefore, has need of our will alone, since it is in us, and is formed from us. For when the soul has its spiritual faculty in a natural state, virtue is formed. And it is in a natural state when it remains as it was made.”

–St. Anthony the Great

The How

So, how is this inner stillness achieved? The most practical and ancient path is through prayer. But what kind of prayer? The early Christians championed the practice of the “prayer word,” most powerfully realized in the humble invocation of the Jesus Prayer.

This is not a mechanical, rigid formulaic mantra, but a constant turning of the heart toward God. It is the practice of calling on the name of Jesus repeatedly, not out of empty habit, but with a real longing to call him and be united with Him.

The prayer can take several forms. While the most common formula is “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner,” the prayer is highly adaptable. The essential element is the invocation of the name of Jesus, so it can be shortened to fit the moment or the individual’s disposition. Many use a shorter version, such as “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me,” or simplify it to its most potent core: the single name, “Jesus.“

The prayer can be adapted to any personal struggle. For instance, when I feel my thoughts being abused by lust, I can say, “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on this heart that hates you and loves lust.” The prayer can be whatever you need it to be. The focus is to keep repeating your chosen prayer word with a true longing until you enter a state of inner stillness. Your mind will inevitably disrupt you with other thoughts, but the practice is to simply keep returning to the prayer with trust and humility. As St. Teresa of Avila advised, we should not fight to remove our thoughts, because the very act of trying not to think is itself a distracting thought. Instead, you simply let them pass and return to your prayer.

But why this specific name of Jesus? Because this is “the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth” (Philippians 2:9-10).

This practice is rooted deeply in the Gospels, particularly in the story of the blind beggar in Luke 18. When the crowd tried to silence him, he refused to stop his plea:

“And those who were in front rebuked him, telling him to be silent. But he cried out all the more, ‘Son of David, have mercy on me!’”

As Father Anthony M. Coniaris powerfully interprets this moment: “If this prayer stopped Jesus then, it can stop Him today.”

As we dedicate time to this prayer, whether spoken aloud or repeated silently in the heart, the inner noise begins to subside. In its place, a quiet sweetness emerges. We begin to experience the truth that “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved” (Romans 10:13). This simple invocation becomes a way of speaking to God in a language beyond our own understanding—the “groanings too deep for words” described in Romans 8:26. It is through this sacred silence that we finally become aware of the Divine Presence.

This path is beautifully illustrated in the classic spiritual text, The Way of a Pilgrim. The book follows an anonymous wanderer whose entire journey is a quest to understand one thing: how to “pray unceasingly” (1 Thessalonians 5:17). He learns that the Jesus Prayer is the key.

At first, the prayer is a conscious effort, a vocal repetition. But as he persists, it descends from his lips into his heart, synchronizing with his very breath and heartbeat. It ceases to be something he does and becomes part of who he is. This is the goal: for the prayer to become so ingrained that it continues on its own, a constant, quiet rhythm beneath the surface of his thoughts, actions, and even his sleep.

When we commit to this practice, the same transformation can occur. The inner silence it cultivates is not an emptiness, but a fullness. It envelops us, becoming a wellspring of God’s grace and strength that equips us to navigate the world. The prayer becomes the anchor in the storm, the sail for the sailor, and the gentle watering for the garden of the soul.

It is the practical means to “pray without ceasing,” transforming our entire being into a living, breathing offering to God.

With practice, the prayer and the silence it brings become the quiet rhythm beneath the surface of our lives. When anger rises, ready to erupt in a reckless word, this inner stillness intervenes. When we are lost in sorrow, the prayer brings a profound and unexpected reassurance to the heart.

This is a spiritual skill. The more we cultivate it, the more deeply we are rooted in it, until we begin to radiate the love of Christ. It is the pure, “foolish” love that genuinely wishes good for our enemies. It is a love that flows not from our own limited capacity, but from the divine source who can “do far more abundantly than all that we ask or think, according to the power at work within us” (Ephesians 3:20).

Let’s commit some time for silence today.

Not running away from reality, but embracing it fully.

Let’s keep it real.

Let’s be real.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

Leave a Reply